What’s in a name?

Well, a lot, but first and foremost: stress. Whether we’re naming our babies, pets, companies, or features, we tend to worry a lot about finding the perfect name. We know intuitively that a name will shape how something is perceived and even influence its direction going forward.

And yet, this stress isn’t equally distributed. In business, people tend to think a lot about the names of the companies they’re building but leave each product and feature name up to whoever thinks of the best-sounding name first.

I think they have it exactly backward.

The real risk when it comes to names is when growing companies name new products and features. The decision seems lower stakes, but a bad product name can split your brand, diluting its power and watering down the impact of the company and product names alike.

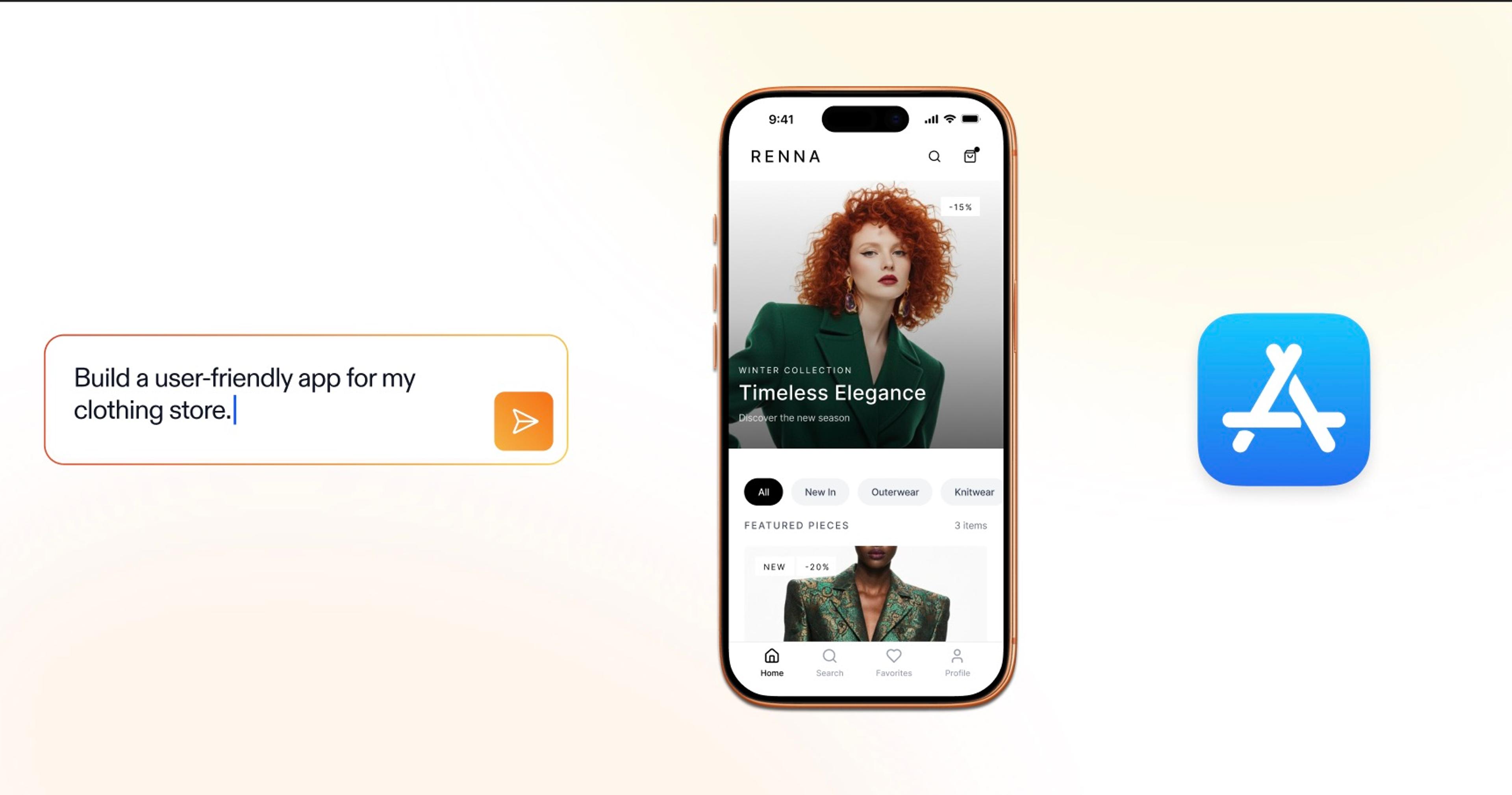

This topic came up just recently when we named and launched Replit Agent, an AI-powered tool that helps software creators use natural language prompts to create applications from scratch.

As our team discussed various names and why one would be better than another, I kept referencing our experiences (and mistakes) with previous names. As we discussed, three core principles rose to the top, and in this article, I want to put a name to them.

Principle 1: Pick names that complement the brand and set the right expectations

Names that complement the brand are better than names that subdivide the brand or introduce competing, confusing, or unrealized ideas.

Google, for example, is a well-established brand that largely sticks to complementary names for new products and features. Google Photos and Google Maps, for example, both set expectations (see Principle 2) and clearly communicate subservience to the primary brand.

(Source)

Google, however, has also become a counterexample with some of its more recent product names and changes. including merging Google Wallet with Android Pay, renaming it Google Pay Send, and then discontinuing it in 2020 after redesigning Google Pay and replacing Tez.

Tesla is a useful counterexample because, while the primary brand is widely recognizable, product names like Autopilot create bad headlines when users assume too much about what the product can do. Technically, the term “autopilot” means human involvement is still necessary, but that’s not what the average person understands – leading to confusion.

A clear, complementary name can leverage the excitement of a new product to support the main brand. The foundation of the established brand can then support the growth of the new product, too. Together, there’s a positive feedback loop that lifts both up.

This was a recent lesson we took from launching and naming Ghostwriter.

(Source)

When we first debuted Ghostwriter, the shock value of the name helped its initial launch period because it went viral, and tons of people tried it.

But we had our doubts. Ghostwriter was too long a name and not as catchy as our other product brands. Though the name helped with initial traction, many users also had false expectations. The name led them to believe the feature would write code for them, but the real purpose was to complete the code they were writing.

These reasons came together and made the choice to change the name compelling. As our new design reflects, our product is AI. The Ghostwriter name unintentionally implied that AI was a side feature.

By renaming Ghostwriter Replit AI, we reset expectations and complemented the main brand in a way that will support both. Now, we can communicate that Replit AI is a core product and that AI will be integrated throughout Replit’s features.

Principle 2: Use realistic names, not fantastic names

Realistic, high-fidelity names are better than names that are fantastical or names that require users to imagine something they’ve never seen before.

When you’re first brainstorming, fantastical names will probably be first to mind because they’ll match the excitement you feel as a founder, designer, or marketer. You have stars in your eyes, and you want the name to reflect that.

But your users (especially your potential users) aren’t there yet. You have to build that excitement through the product.

The name is a tempting shortcut. Many companies name products based on aesthetic values alone—what the name sounds like or the associations it evokes–because it seems like those names can communicate the product before users even get their hands on it.

But the opposite is true: Names that sound cool but don’t communicate anything concrete often leave users struggling to understand and remember what the product really is.

Take the Apple Pencil, for example. The Apple Pencil is just that—a pencil for Apple devices. Users can intuitively understand what the product is and what it does. They won’t know the ins and outs or their particular use cases, but they can imagine holding it in their hands.

(Source)

Similarly, when the original iPhone was announced, users understood that it was, on some level, a phone. Unlike the iPhone, a Blackberry needs more context before it becomes understandable.

By using names that users are familiar with in everyday life, you can:

- Communicate the core functionality of the product.

- Create a level of fidelity that makes an unseen product feel tangible.

- Frame how users will see and initially use the product.

The last point became a big lesson for us when we named and renamed our community. Initially, we called it I Built This, and the name worked as the name implied. Most of the community were people who had built things and wanted to share them with other builders.

Later, we added Ask, a forum for asking and answering questions, and renamed I Built This to reflect a broader pool of users and called it Community.

Back then, we learned first-hand that user behavior significantly changes when you change a name. The more realistic and concrete the name, the more you can learn from the behavior you encourage and the better you can shape that behavior with new names.

Principle 3: Focus on sticky names, not delightful ones

The last principle sounds obvious but is easy to forget once you’re brainstorming names on a whiteboard: A name will likely never delight anyone, so you should instead focus on making it memorable.

When you start thinking of names, it’s easy to slip into thinking of the work as finding a name that will resonate, impress, or astound. Brainstorm too long, and you can find yourself working on a Don Draper pitch when you should be working on finding something that just sticks.

The pressure is misplaced because the name won’t delight. The product will delight.

The name only needs to be memorable and sticky enough for potential users to remember it and hopefully try it. Apple—always one of our biggest inspirations—doesn’t have a company name that blows anyone's mind, nor does it debut products with names (iPhone, iPad, Mac) that astound people. But the names stick and it’s always clear when someone is talking about an Apple product.

So far, we’ve focused on product and feature names, but we actually learned this lesson way back when we first named Replit. The company's first name was Replit, but soon after starting the company, we considered renaming it Neoreason.

(Source)

Replit had good but potentially worrisome associations. REPL is a concept in Lisp, which meant that for some users, Replit did communicate our love for developers, but it might have also communicated some level of exclusivity with Lisp.

Back then, we didn’t have the resources for focus groups or market testers. Instead, I walked from coffee shop to coffee shop and presented everyday people with the options side by side.

I thought Neoreason might stand out better–especially because none of these people were technical–but Replit won out. People struggled to read Neoreason at first glance, whereas Replit was short, quick, and easy to parse.

Here, we learned that the stickiness of a name is more important than anything else and that a name has to match the spirit of the company.

Naming a product, feature, or company is like naming a person – despite many other factors, the name and the initial impression it makes will influence how people think about it. A name can’t be pre-selected from a list; it has to suit the personality of what you’re naming, even if the personality is still developing.

At the time, the Replit “personality” and brand were nascent, but they meant something to our early users. They turned Replit into a shortcut and started calling programs built in Replit “Repls.” The initial name stuck, and its stickiness remains today.

Names support brands, not the other way around

The stakes for a new name are often high. Everyone wants a vote, and you can easily get locked into a “design by committee” dynamic.

But while the stakes of the name are high, no name is permanent. Renaming a product takes some work (which is why we’ve developed these principles to make renaming less likely), but the benefits of a good name make rework worthwhile when it’s necessary.

Remember, a brand is not a name. A company brand is built over years of work building a product, serving customers, and fulfilling a promise the brand continuously makes.

If your brand is making a promise you want to keep or, later in the company’s life, making a new promise to align with new realities, then it only makes sense to rename the company, feature, or product. Names are important, but they serve the brand first and foremost.