In our previous blog post about Worldwide Repls, we talked about how we revamped part of our infrastructure to build a new abstraction that allowed us to build other components on top of it: the control plane. In this entry, we'll talk about the very first thing we built on top: a load balancer.

The need for an alternative load balancer

All of our infrastructure currently runs in Google Cloud Platform, and it comes with several options for very robust load-balancing across services in the form of the Google Cloud Load Balancer (a.k.a. GCLB). Since it's very easy to get started, that's what we used for several years. It has all sorts of very neat features like SSL termination, geographical routing to minimize latency, integrates with their autoscaling solution to let us grow and shrink the size of our fleet to reflect the number of concurrent users, and is even optimized to support a request load that is not quite homogeneous: a few requests that are 10,000x more expensive than others is totally supported.

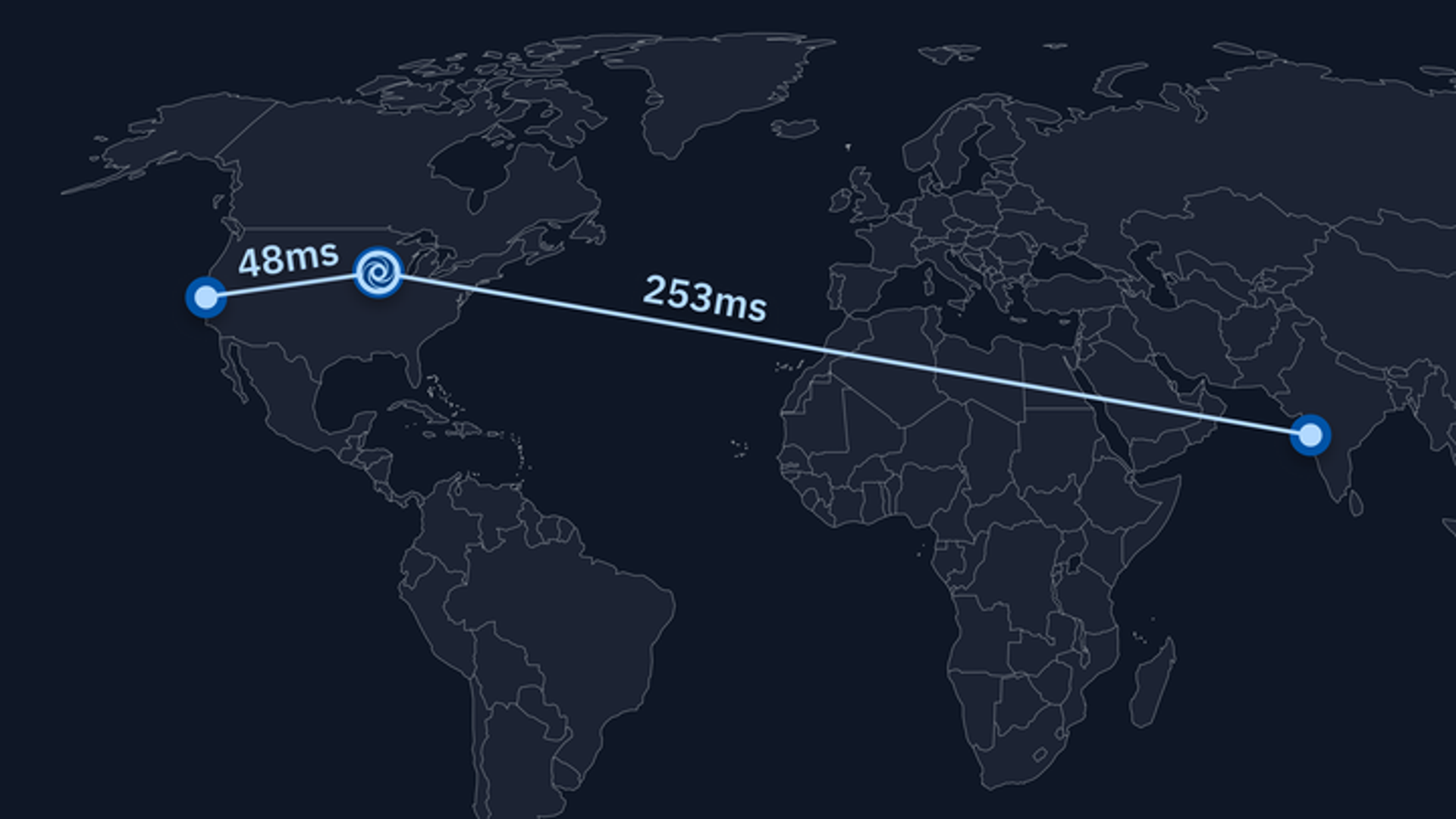

So far everything looks great on paper. Why did we need an alternative load balancer? When we originally announced that we were going to support non-US compute regions, we discovered that there was a small disconnect between how the GCLB operates and how we would like it to operate: back then, when a user made a request to start or connect to a container, the container would be created geographically near where the user made the request if possible, and would fall back to where we had capacity. This unfortunately meant that there were several cases where a user in India would start a container, it was created in the US, and all network packets would still need to perform one earth-sized roundtrip. To make things worse, this also happened to some folks in the US, so we had to revert that change.

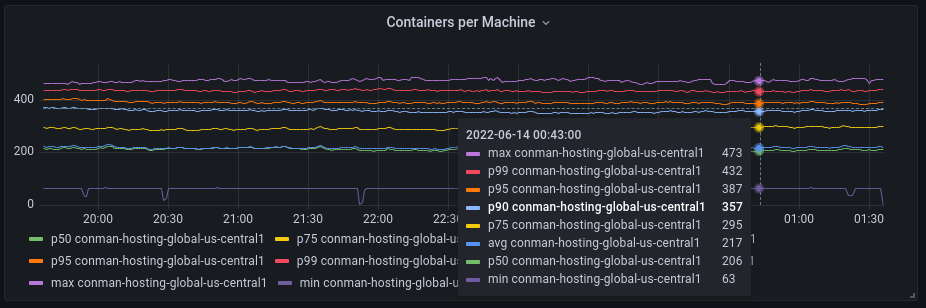

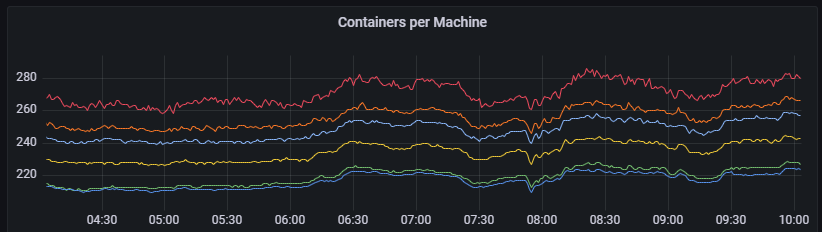

By this point in time it was clear that we had to create an intermediate layer that could allow us to make decisions as to where the containers were created, since we had all the information about the Repl upfront, but GCLB alone was not able to use this information. A bit later, our team of SREs found something even more disturbing: the distribution of load across our fleet was all over the place!

What this means is that a proportion of machines are being overloaded and providing suboptimal service to users, and other machines are being underutilized. This meant that a proportion of users would get a bad experience and were seeing both slower Repls, and also have those Repls be less stable due to spurious timeouts that happen when a machine is overloaded. So now we had two reasons to roll our own.

Building a prototype

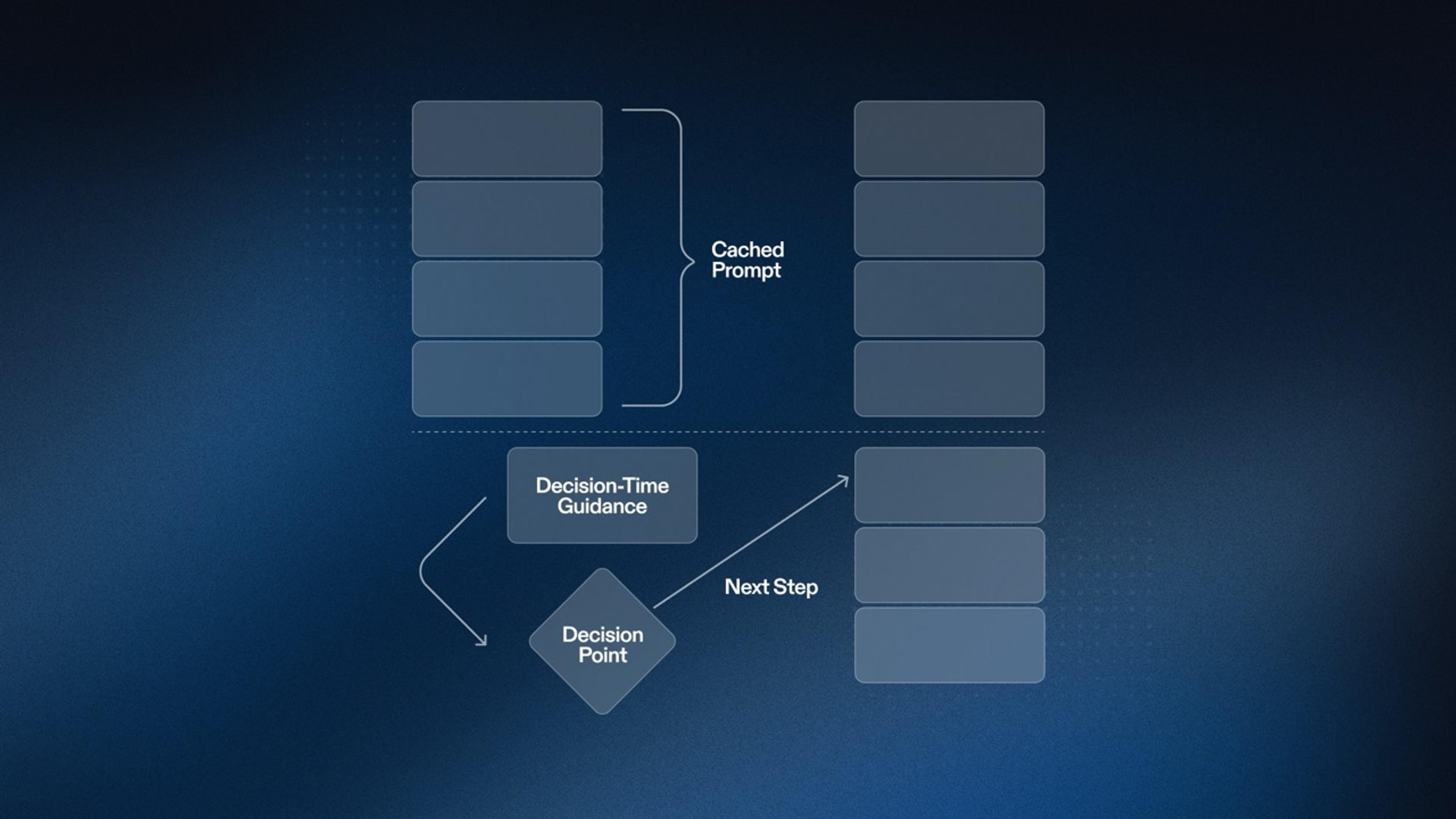

Step zero was to build a proof-of-concept just to make sure that we weren't going to make things worse. With all proof-of-concepts, you want to actively cut corners just to see if the idea is worth pursuing. Our SRE team built something in a Repl using a very simple concept: subsetting. A theoretically optimal load balancer could place requests in the machine that's the least-loaded at any point in time. But that doesn't scale, since it means that every time a request is made, the load balancer needs to inspect every candidate and grab its utilization stats. So in order to have this process scale a bit more, every so often we choose a subset of all the available, healthy machines that we can send traffic to and then choose the actual machine the request is going to go to based on another policy (random and round-robin are two popular policies).

The initial proof-of-concept was done by scraping our Prometheus metrics server from a Repl to get the set of all available + healthy machines as well as a few more stats (CPU utilization, number of Repls already in the machine) and apply the subsetting algorithm to it. We then compared this choice against the one made by GCLB. We were surprised by the results!

Container count variance greatly reduced between median and 99th percentile

What was happening? Were we holding it wrong?. It turns out that there were several things going on at once, but we hadn't noticed them at the time, mostly because this is a very opaque system that we don't have a lot of visibility into. So it's time to add a bit of observability by building a simulator. Since we don't have the exact algorithm that GCLB uses, all we had to go on was this little high-level explanation in the public documentation. But that's better than nothing: we can still compare our best guess of what it's actually doing against some observations in production.

Lo and behold, even in a simulated context and with tons of wild assumptions and simplifications, our guesses were pretty close to what we were observing in production. We even threw in a couple of corner cases that we had seen recently (an unfortunate combination of big and small Managed Instance Group in the same load balancer) and we managed to reproduce roughly the same high-level behavior. Now armed with a simulator, we were able to go and throw a lot more hypothetical cases at the system, including different subsetting strategies and a lot more tweaks. We were making a ton of progress and managed to avoid a few conceptual bugs from creeping into production just by doing this toy simulator first. During this phase we discovered one more way we were using GCLB in a way that wasn't quite amenable to how it was designed: every connection could have massive load differences, up to 6 or 7 orders of magnitude! A short-lived Repl started from Spotlight doesn't consume a lot of resources on our side, but a Boosted, Always On Repl essentially lives forever. This (likely) exceeds GCLB's ability to correctly place requests in the right VM.

Pushing it to production

In theory, just porting the prototype / simulator code to production should have sufficed and made everything instantly better. In practice, there were a couple of speedbumps. Our initial subset size was originally set way too low and we weren't refreshing the subsets fast enough, so a period of relatively high utilization (like a Monday morning when there are lots of schools starting) could take a few machines out pretty quickly. Luckily we had planned for this case by flagging the load balancer implementation used, so we had a quick path to safety.

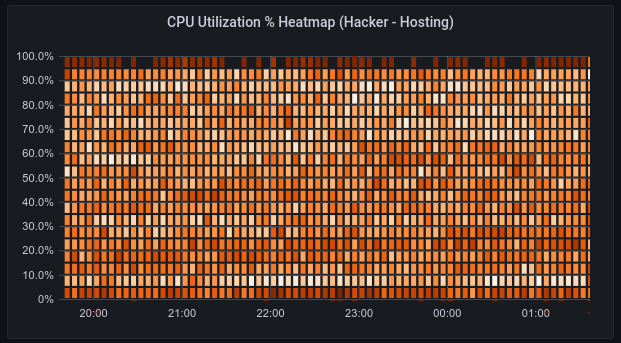

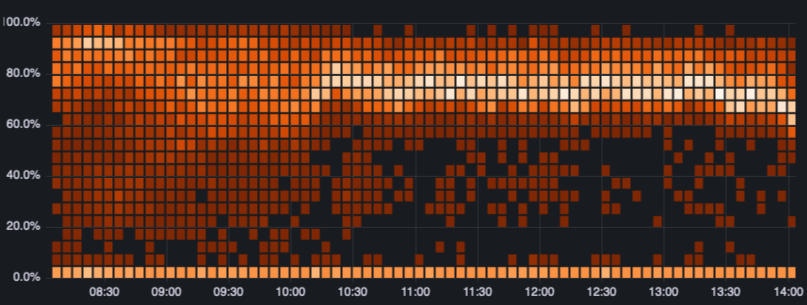

After a couple of weeks of finding and fixing bugs we are now pretty happy with the results. Our the resource utilization uniformity of our fleet is at an all-time high, and we also happened to almost completely eradicate some spurious errors we had been seeing for months, that we now know are caused by having a choppy influx of requests into a few machines. Here's the final image when we enabled the last few percent of our own load balancer (a histogram of machines' CPU utilization)

What's next?

This utilization uniformity was a very nice bonus, but the original goal of supporting better geographical distribution is still ongoing. Eagle-eyed viewers might notice that there's a dense band of machines at the bottom which shouldn't be there. And you're right. Those are a few machines that are geographically distributed and are lying in wait for us to finish a few more changes to start sending traffic to them.

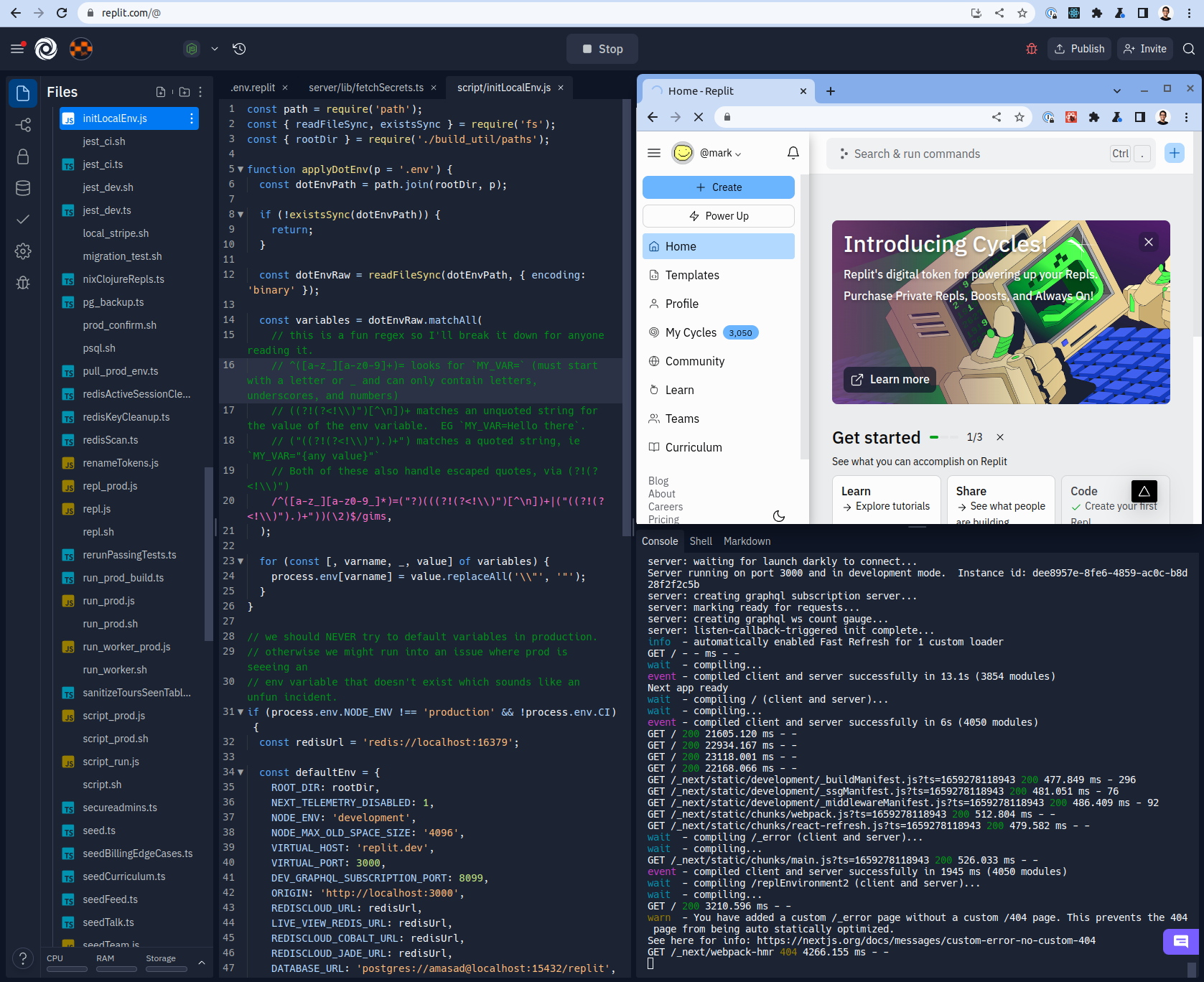

Now that we have one more primitive, what else are we building with it? To start, we're putting the final touches around a change that enables vertical scalability: imagine a world where you can buy more powerful Repls, Repls with more CPU and RAM than what a Boosted Repl can provide. And to prove that works, here is something we have been working on for a while. An answer to the most-commonly-asked question when we interview folks: "so... are you running Replit on Replit?" And for the first time, we can unironically say "why yes. yes we are!"

Loved what we're working on? Want to be part of the next big thing we're building? Consider applying, we're hiring Platform Engineers!