We know that games are an important part of our commitment to making programming more accessible, more creative, and more fun. Back in February when we announced a significant revamp to our graphics stack, we also promised that we would also provide system audio integration. That support is finally available today, as an opt-in feature.

How to opt-in

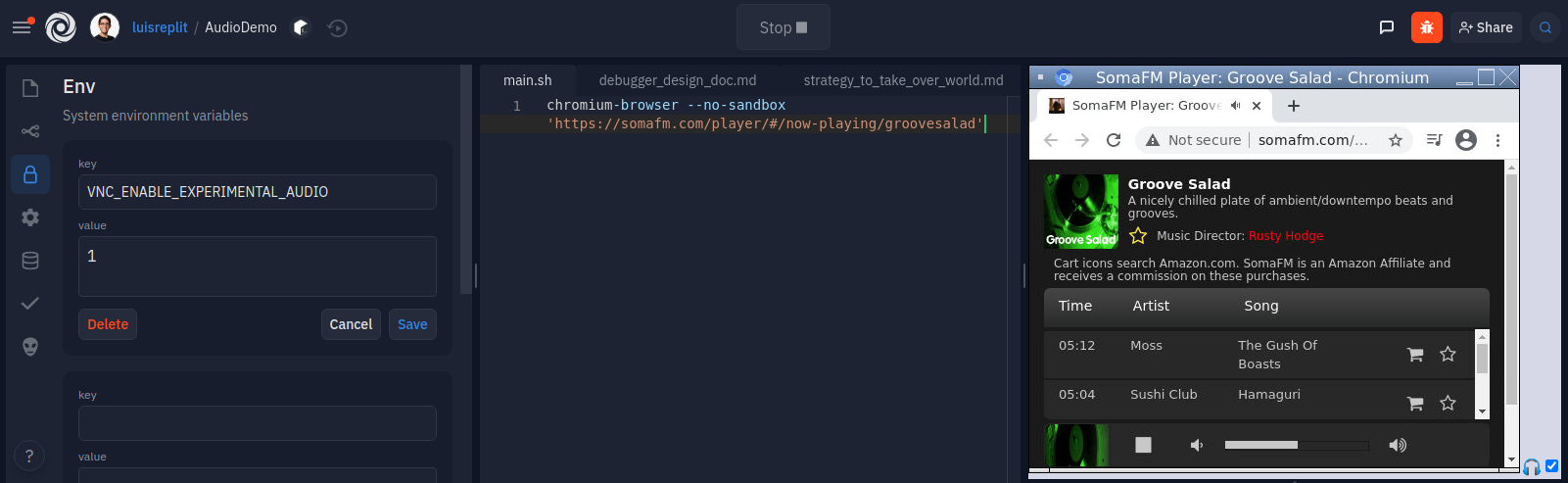

We are firm believers in the "Don't pay for what you don't use" philosophy. Since enabling system-wide audio is moderately expensive, resource-wise, it's better for this feature to be opt-in. In order to do so, all you need to do is create a secret called VNC_ENABLE_EXPERIMENTAL_AUDIO with a value of 1 and restart your repl by running kill 1 on the shell. Once that's done, a checkbox with headphones will appear in the lower right corner of the VNC output window:

Due to restrictions in the browser security model, there needs to be an explicit user interaction when enabling the audio, which means that the checkbox needs to be manually toggled every time the repl is opened.

How does it work?

Linux (and other POSIX systems) users will probably be familiar with PulseAudio as the main component in the desktop audio experience, with compatibility layers for other sound systems like ALSA. It's the userspace solution that has the widest support for gaming libraries and desktop applications. A few months ago when we decided to support audio in a system level, there was no pre-existing end-to-end way to get compressed audio from PulseAudio delivered alongside Remote Framebuffer, the protocol that we use to display the graphic repls on the workspace.

So we set out to build that support. The easiest way to achieve this was to bundle the audio data inside the VNC connection using an RFB protocol extension, similar to how QEMU used to do this before they switched to the SPICE protocol. That only allowed for uncompressed audio, which consumes a lot of bandwidth, so that was not an option for us. We also didn't quite want to maintain a set of floating patches for the VNC server that we use (X11 / XtigerVNC) so that it would be able to embed the audio data. One way to achieve this with minimal maintenance is to splice the audio data outside of that process: we were already using an external process (Websockify) to convert the RFB connection from a raw TCP stream into a WebSocket connection, so changing that component for another added no extra overhead. Furthermore, since we wanted to change how the VNC authentication worked, it meant that both efforts would benefit from this change: This is how our RFB proxy written in Rust was born.

rfbproxy connects to both XtigerVNC and PulseAudio, transcodes the audio into an Opus stream in a WebM streaming container (with an MP3-in-MPEG fallback for browsers that don't support Opus/WebM), and delivers a unified RFB stream to the NoVNC client.

Here's a snippet from the original design doc, that illustrates how all pieces work together:

[ Client app ][ALSA library] --(config files)--> PulseAudio --\

| [PulseAudio library] -----------------------^ |

| |

\-------------------> XtigerVNC |

| |

v |

/----------------------- rfbproxy ------------------------/

|

\----------------------- RFB WebSocket

|

v

NoVNC + Web Audio

Extending a web protocol needs to be done with coordination with the rest of the community, since the changes could accidentally conflict with other projects. Fortunately, the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority helps with that by maintaining a canonical list of extensions to most protocols. A few weeks ago, we were granted assignments for the messages required to implement the Replit Audio extension in the RFB protocol, so at that point we were finally able to move forward without fear of breaking things for anybody!

Known limitations

The Web Audio API in most browsers have a buffer of 100-300 msec which we haven't found a way to reduce, so there is a 100-300 msec worth of latency that is added to the audio when compared against the video. There are also some known issues with Safari playback, since their security model is slightly different than Chrome or Firefox. Finally, due to OS scheduling and other resource constraints, non-Hacker repls may not be powerful enough to provide a smooth playback.

Happy gaming!