How Replit built a novel REPL-based verification system that combines code execution with browser automation to catch "Potemkin interfaces" (features that look functional but aren't), enabling Agent 3 to work autonomously for 200+ minutes.

In 1783, Russia annexed Crimea from the Ottoman Empire.

With war looming, the Russian Empress embarked on a six-month trip with several foreign ambassadors to garner more support. Grigory Potemkin, the minister responsible for rebuilding the region, realized the Empress and her visitors would never actually go ashore. He devised a scheme to hide the war-torn landscape by constructing "mobile villages." His men would dress as residents when Catherine's barge arrived, then disassemble the village after it left.

Potemkin realized it was much cheaper to create the illusion of a vibrant town than to actually build one. If the people looking at the output don't look that close, why do more work than you need to?

This effect has been observed across centuries and has been called many things. Reward hacking. Goodhart’s Law. Rational expectations. The Lucas critique.

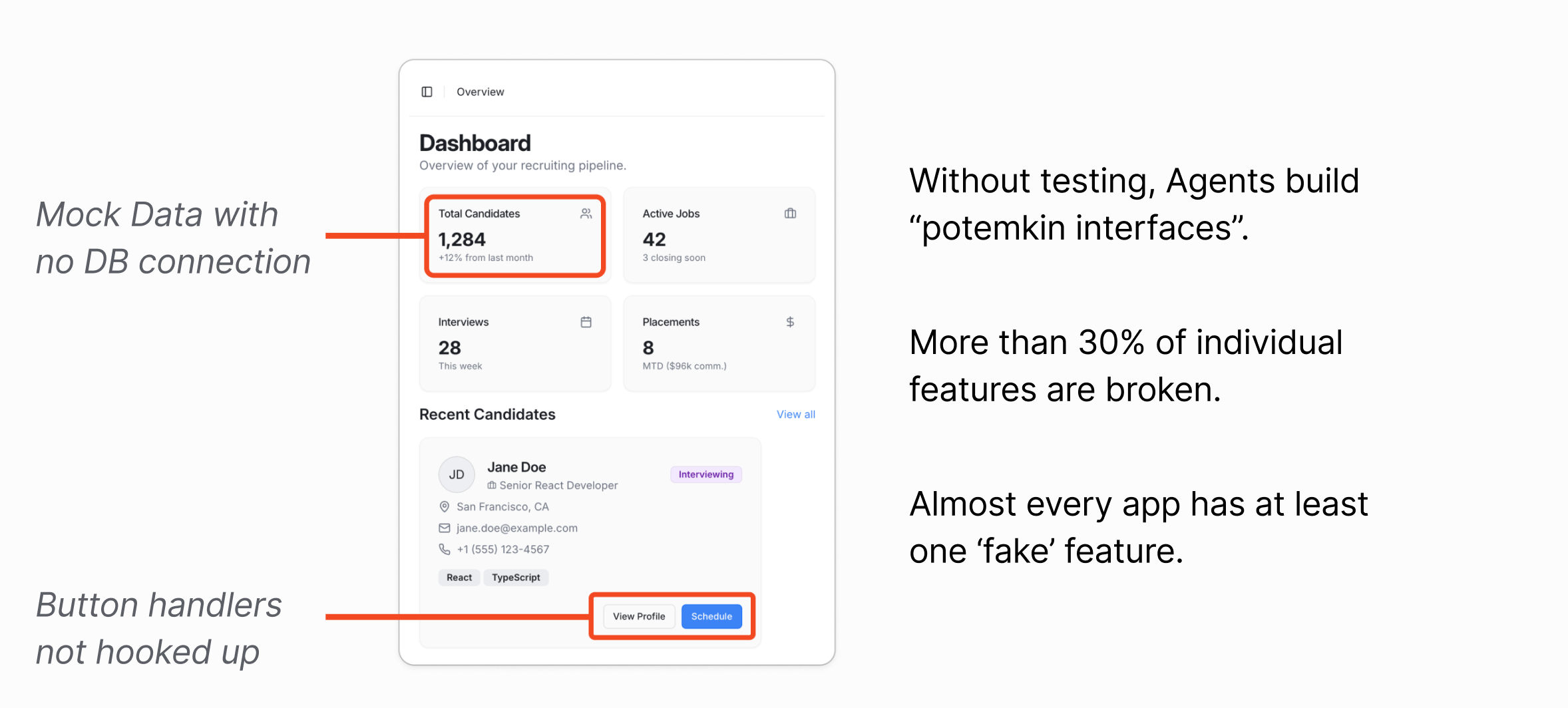

As we started working on Agent 3, this failure mode became more apparent, with the model generating what we call Potemkin interfaces. A feature that the user requested may appear to work on first inspection: buttons render correctly, dashboards display statistics, and the UI responds to interactions. But further interactions reveal that nothing is hooked up. Event handlers are missing, the data is mocked, and links go nowhere.

These Potemkin interfaces are particularly dangerous because they pass as working on first glance. A user might not realize their application is fundamentally broken until they try to use it in production by which point the Agent has moved on, compounding its mistakes with each subsequent feature built on a faulty foundation.

The Verification Spectrum

The crux here is that nothing prevents the Agent from giving back a nice-looking but completely non-functional frontend to the user. While this may work for a lot of code generation Agents that just aim to produce something that looks nice, Agent 3 tries to build things that both look great and are fully functional.

It turns out that the best way to deter these Potemkin outputs is to get better at catching it and calling it out.

Agent-based shift-left testing

There’s a concept in software testing called ‘shift-left testing’ which was coined by Larry Smith in 2001. The idea is that developers should aim to test earlier in the lifecycle (left on the project timeline) where it is cheaper to catch bugs than later in the process.

A key insight for us was that as the Agent became more autonomous, the more important verification became. Without robust verification, mistakes compound. An agent that builds a feature by taking shortcuts will only proceed to take more shortcuts to build on top of a broken foundation.

As we developed Agent 3, we realized that to hit our autonomy goals, we needed much better mechanisms for the Agent to self-verify if what it was doing was correct or not — we need to shift-left.

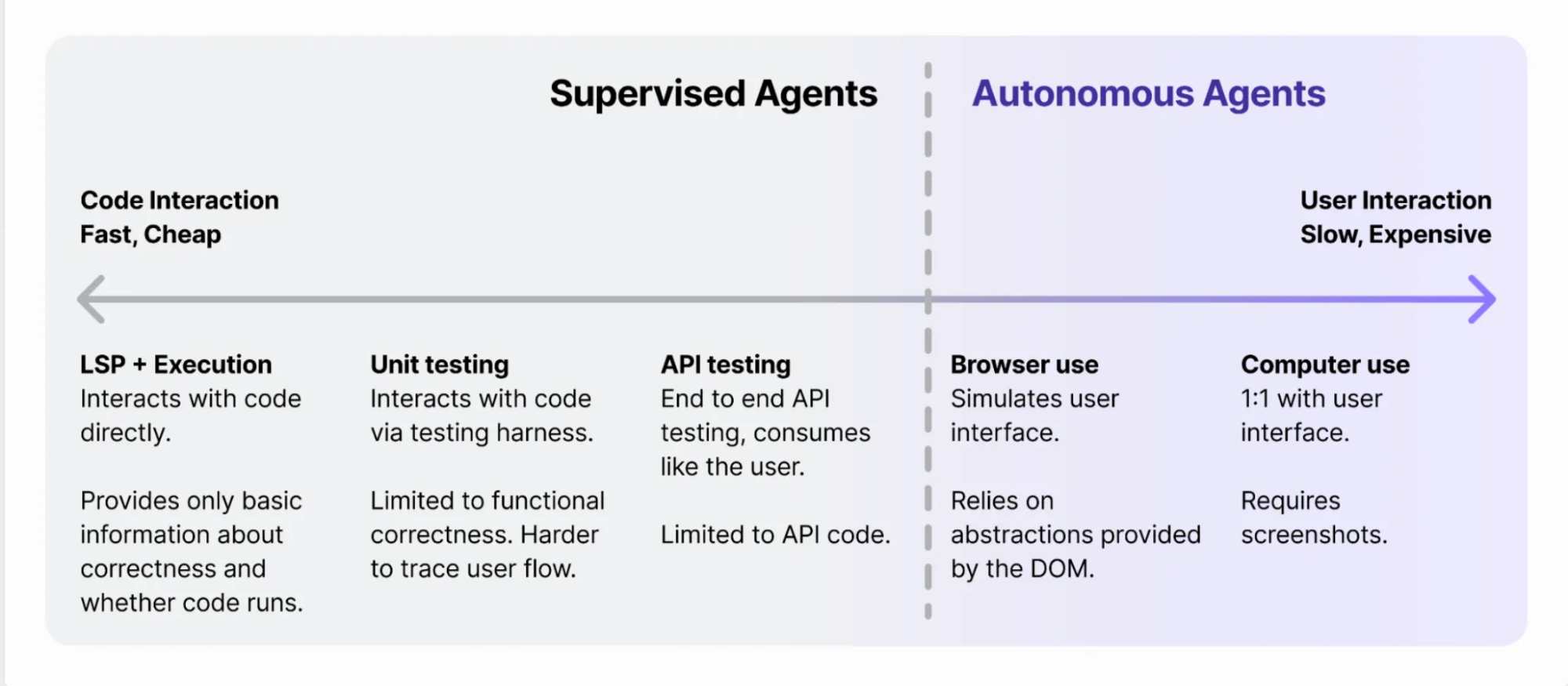

If you look at the first 2 levels of code verification, you’ll notice that most of the testing is limited to very narrow flows and functionality within the application.

- LSP + Execution concerns itself with syntax-level correctness

- Unit testing concerns itself with basic functional correctness

As we move to API testing, we start testing larger swathes of functionality from the server’s perspective but still miss how the actual client might call those endpoints.

Lots of apps require a complicated dance to coordinate client-side state and server-side state and it’s at these seams where traditional testing falls apart. Testing user interfaces to make sure they construct the right data to send to the backend, auth that depends on browser cookie behavior, client-side caching and revalidation are just the surface of the mess of problems that lurk at this boundary.

The natural question to ask then is how might we push this verification boundary even more to the right so that the Agent has visibility into these bugs that are otherwise undetectable via the previous approaches.

Browser-automation-based testing

One approach is to copy what human developers have been doing for years which is using browser-automation-based testing frameworks like Playwright, Puppeteer, and Cypress to programmatically express client actions (“click on the Sign Up button”, “fill out the form with the following information”) and expected outputs (”make sure text that says ‘Success’ eventually shows up”). Because these frameworks operate at the browser-level, they emulate real user events quite closely and are really flexible in terms of representing user flows.

import { test, expect } from '@playwright/test';

test('booking form', async ({ page }) => {

await page.goto('/booking');

await page.getByLabel('Name').fill('John Doe');

await page.getByLabel('Email').fill('[email protected]');

await page.getByLabel('Date').fill('2024-03-15');

await page.getByLabel('I agree to terms').check();

await expect(page.getByLabel('Name')).toHaveValue('John Doe');

await expect(page.getByLabel('I agree to terms')).toBeChecked();

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Submit' }).click();

await expect(page.getByText('Booking confirmed')).toBeVisible();

});Why not just get agents to write these tests?

It turns out that actually writing these tests in one-shot is very hard, especially if you had to do it without seeing what the actual website looks like! Most QA engineers have a process that involves iterative cycles of:

- Visually inspecting the page and figuring out what labels and DOM elements need to be interacted with to get to the desired state.

- Writing the code to perform the actions and asserting the desired state is reached.

Without tools to do the first point, agents run into loops trying to understand how all the code it had written previously translates to the DOM.

This has legs but doesn’t get us all the way there. What if we tried to push the boundary even more to the right?

Browser-use

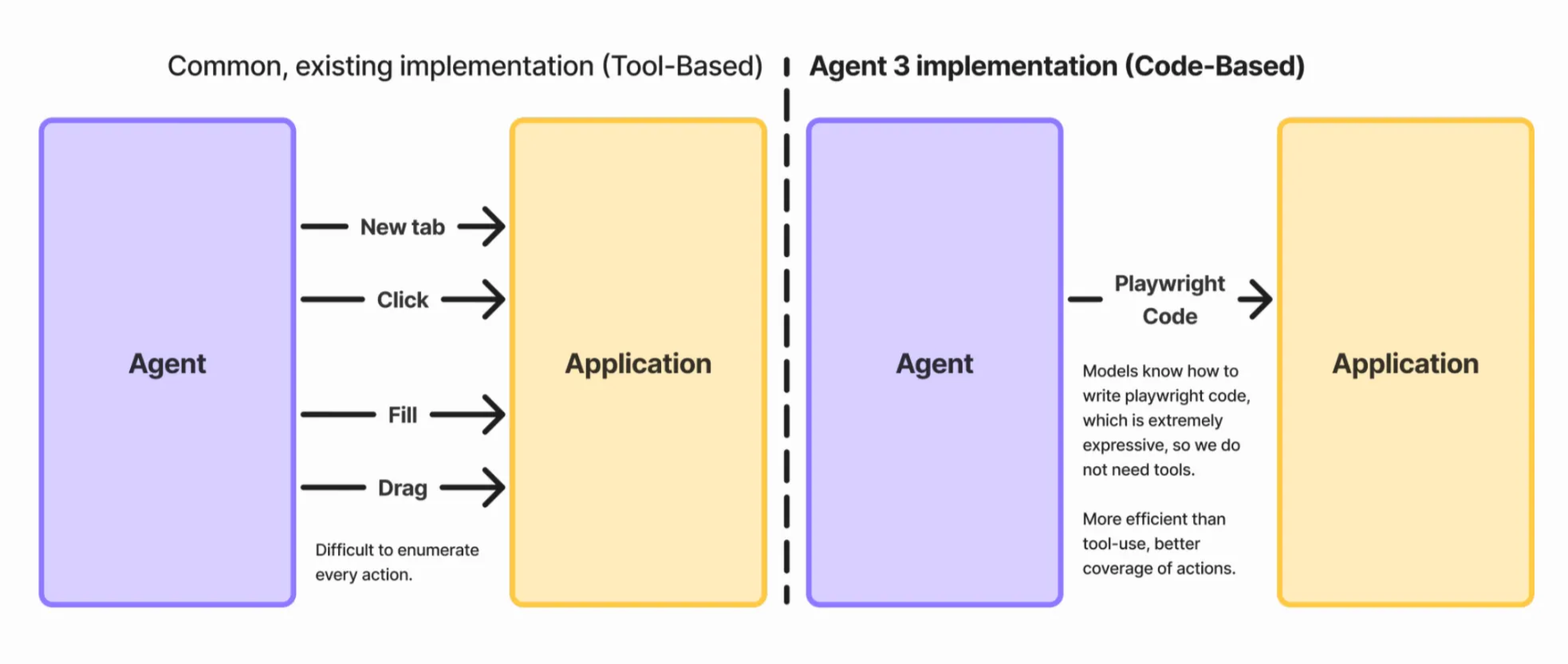

One approach is to expose the browser-automation frameworks above as tools that an agent can use. Projects like Playwright MCP, Stagehand, and Browser Use take this approach by wrapping browser automation primitives (click, type, navigate) as discrete tool calls that agents can invoke. The agent requests to click a button, the framework executes that action, and returns the result.

However, this approach has limited expressivity. Want to upload a file? You need a new tool. Want to open a new tab? Another new tool. Each tool consumes precious context that our users are paying for, and the action space of what the agent can do is constrained by what tools are available. Complex workflows become unwieldy to express as sequences of individual tool calls, even if the model itself can support parallel tool-calling.

End-to-end computer use

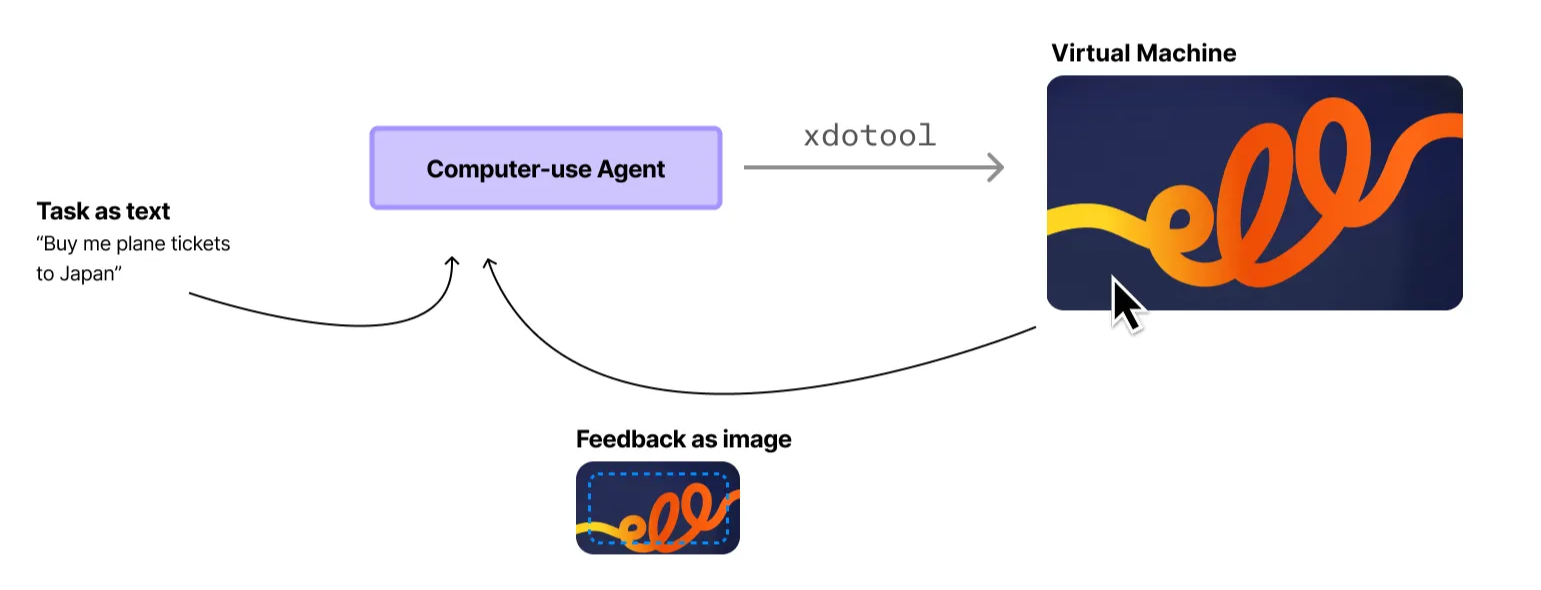

Labs have started to fine-tune models to act as computer-use agents (CUAs) that interact with computer interfaces like a human would by looking at the pixels on the screen, clicking, and typing.

These models are still relatively new but have shown impressive ability to be domain-general enough to reason about complex game GUIs, elaborate multi-step user flows, and temporal/causal coherence.

While the quality of the results have been good, the speed and cost make it prohibitive to deploy in real-world settings. With some rough back-of-napkin math (assuming Claude Sonnet 4, 1080p screenshot resolution, multi-step context window accumulation with ~1k tokens to represent the DOM) we’re looking at roughly $0.50 and 30-90 seconds to fill out a 5-field form.

Automated app testing in Agent 3

What if we could combine the strengths of both approaches? We saw how CUAs were able to interleave exploration with verification to be more robust and wondered if we could blend that with the efficiency gains that code-based browser automation could provide.

Code use

What if instead of tool calls, we used code to express our actions instead? We could allow the agent to execute JavaScript in a sandbox and inject helper functions that allow it to manipulate the browser using Playwright.

const context = await newBrowserContext();

const tab1 = await context.newPage();

const tab2 = await context.newPage();

// Tab 1: Start booking

await tab1.goto('/booking');

await tab1.getByLabel('Name').fill('John Doe');

// Tab 2: Check availability in parallel

await tab2.goto('/availability');

await expect(tab2.getByText('3 slots available')).toBeVisible();

// Tab 1: Complete booking

await tab1.getByRole('button', { name: 'Submit' }).click();

await expect(tab1.getByText('Booking confirmed')).toBeVisible();

// Tab 2: Verify availability updated

await tab2.reload();

await expect(tab2.getByText('2 slots available')).toBeVisible();

Playwright is extremely well-represented in LLM training data. This property means that models already know how to write Playwright code and understand the semantics of how to use it without additional prompting.

Code execution also means we directly borrow from the token efficiency gains of browser-use. Complex sequences become simple loops, allowing for elegant handling of repetition, conditionals, and guards. Consider a practical example: selecting December 15th, 2028 on a calendar widget. Starting from today, this requires navigating forward roughly 36 months.

With traditional browser use or computer use, the agent needs to make 36 separate actions, each requiring a call to the upstream model. That's slow and expensive. With code use, this becomes a single model call to generate some code:

for (let i = 0; i < 36; i++) {

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'next-month' }).click();

}

await page.getByRole('button', { name: '15' }).click();Putting the REPL back into Replit

Code execution by itself already nets us nice wins for token efficiency but truly shines when we expose it in a notebook interface to the agent.

Recall from earlier that one of the main difficulties of browser-automation-based testing was teaching agents about how their previously written code would translate to DOM state it needs to then act on.

In a notebook, the persistence of the execution environment between interactions unlocks an iterative approach to testing:

- Variables persist: Information from earlier interactions can be used in future ones

- Browser sessions persist: The agent can gradually explore a webpage and perform actions on the same browser instance based on earlier observations

- Context stays in code, not in tokens: For example, when testing an e-commerce app, the agent might simulate buying a product and capture the order ID. Later, it needs that ID to verify order status.

// execution 1

let orderID = await completePurchase(cart);

console.log("Order placed");

// agent goes and ruminates

// execution 2 is in the same scope as execution 1

await page.getByLabel('orderNumber').fill(orderID);

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Search' }).click();In the agent loop, the agent has options to both validate assumptions about the state of the world that aren't clear (e.g. is there an element with the role 'button' on the page) and manipulate it (e.g. press a button, fill out a field, navigate to a page). With this, we saw a notable increase in the complexity of apps and user flows the agent was able to test successfully.

More state information

In addition to code execution, we found augmenting what the agent had visibility into was helpful in pinning down otherwise hard-to-spot bugs and helping it generate more token-efficient test code.

- We provide the agent with a stripped-down DOM representation that is augmented with ARIA labels and test attributes. Additional prompting to the main agent to add these attributes to important interactive elements like form fields and buttons when generating them.

- We inject additional utilities functions into the notebook context like the ability to do read-only queries against the application’s database.

- We also capture any new client and server logs since the last execution. This helps the agent establish cause-and-effect relationships and adds print style debugging to the agent’s toolkit.

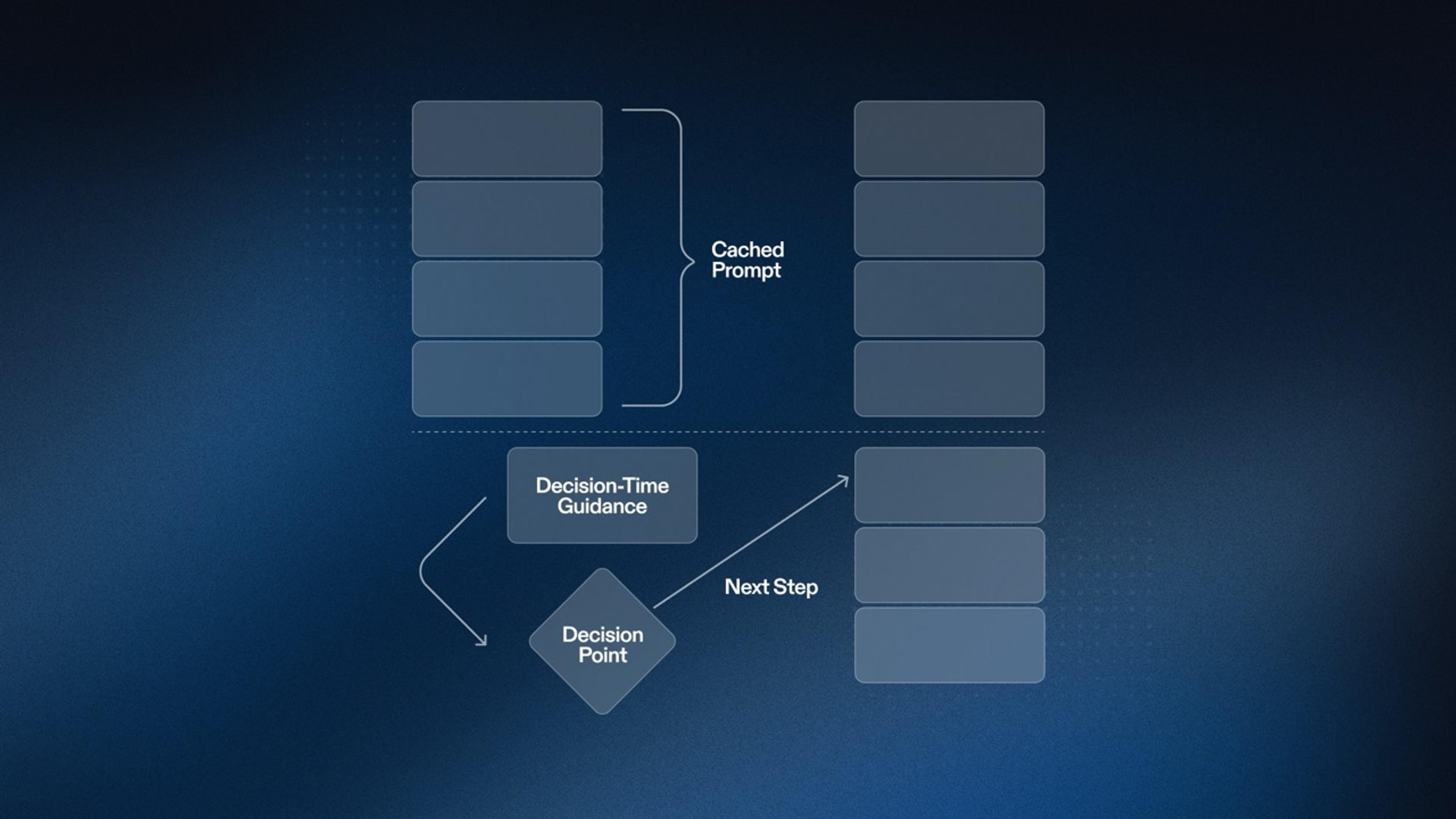

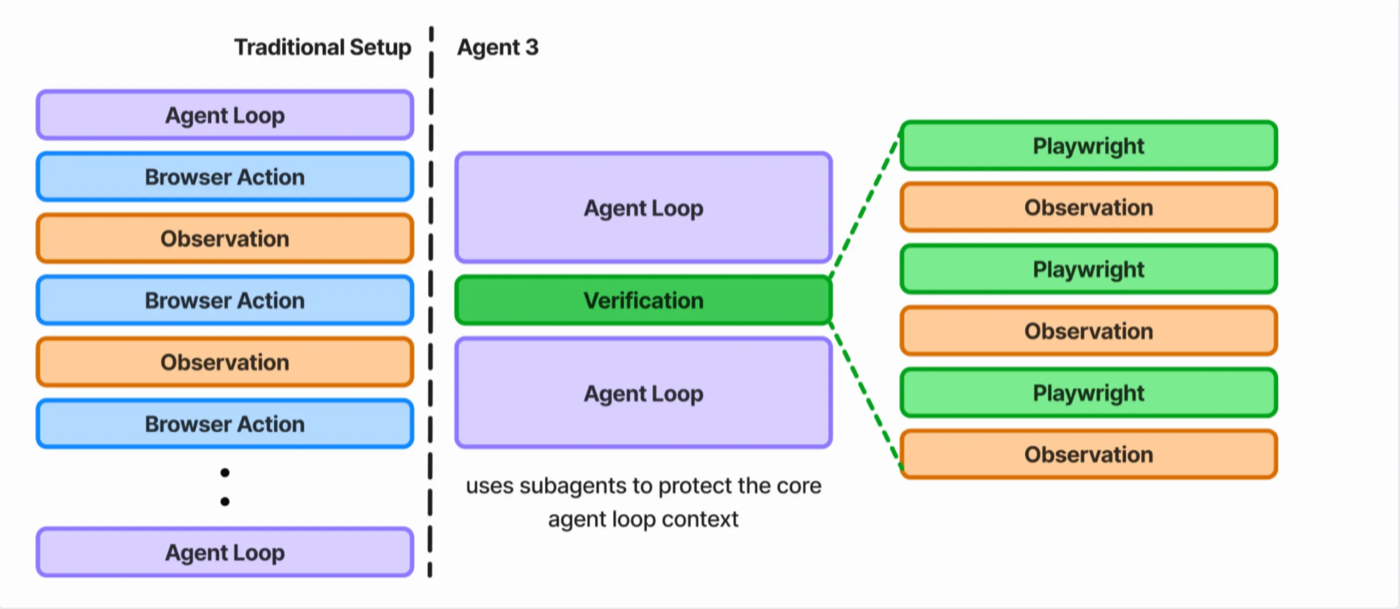

Testing as a subagent

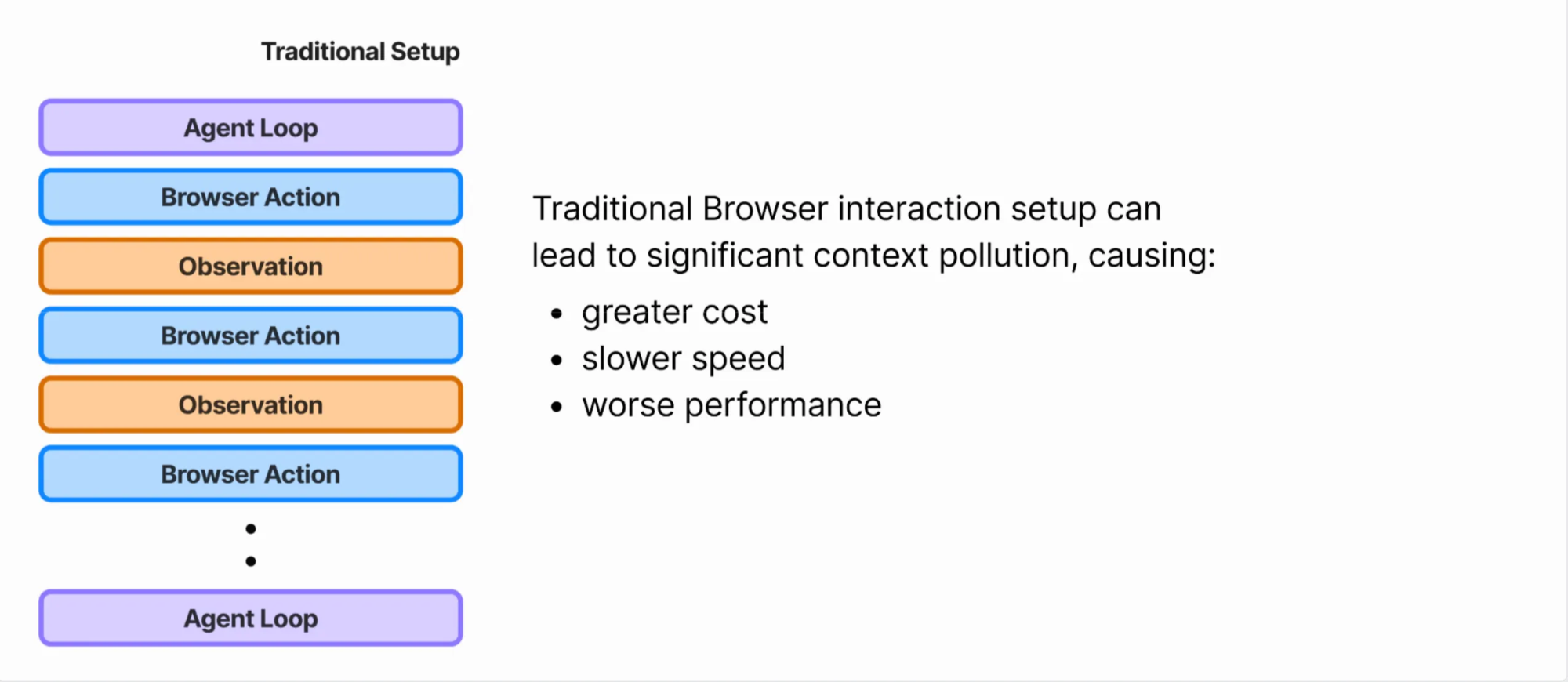

Programming is token-intensive. The main agent context often reaches 80,000 to 100,000 tokens as the agent reads files, writes code, and manages project state. If we made testing part of the main agent loop, our context would get polluted extremely quickly.

This creates a context pollution problem: during testing, the agent would have carry all existing context of working on the app, most of which is irrelevant to the testing task. Then, after testing, it needs to carry all the context about the testing session back into writing code. This additional irrelevant context significantly decreases task performance.

To solve this, we split the testing task out into a separate subagent. The main agent and testing subagent communicate by only passing the necessary context needed for other to do its job.

At a high-level:

- The main agent kicks of the subagent by giving it a plan with high-level actions.

1. Start from /products

2. Assert product displays with correct price

3. Adding to the cart works- The subagent follows the standard agent loop of action, observe, repeat until it deems testing to be complete.

- When returning to the main agent, we summarize the testing and provide guidance about what works and what's broken.

200 minutes of autonomous runtime

One of our claims of releasing Agent 3 was that we made Agent 10x more autonomous, bringing the total amount of time it’s able to do productive work completely on its own from 20 minutes to over 200 minutes.

At its core, that achievement is in part enabled by this new hybrid testing technique we’ve developed for Agent 3. By synthesizing these techniques, we’ve created a self-testing flow for the Agent that is able to perform complex, multi-hundred step testing at a median cost of $0.20 per session.

It helps check the Agent’s work and calls it out when it cuts corners. In doing so, the Agent produces apps that are not only beautiful, but work as you’d expect. Buttons that click. Data that persists. Features that work.

The real app, not just the illusory Potemkin facade of one.

Work at Replit

Find this blog post interesting? Come work with us to solve technically challenging and highly ambitious problems like these, and enable the next billion software creators.