The technological singularity—or simply the singularity—is a hypothetical future point in time at which technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unforeseeable changes to human civilization. According to the most popular version of the singularity hypothesis, I.J. Good's intelligence explosion model, an upgradable intelligent agent will eventually enter a "runaway reaction" of self-improvement cycles, each new and more intelligent generation appearing more and more rapidly, causing an "explosion" in intelligence and resulting in a powerful superintelligence that qualitatively far surpasses all human intelligence. — Wikipedia

In normieland, where I still spend plenty of time both online and IRL, software’s newfound ability to write, draw, and speak like we humans is often taken as evidence that the machines are about to remake our entire society (again) and totally change the nature and value of labor (again). I don’t think the normies are wrong about this, but as flashy as Stable Diffusion and ChatGPT are, old heads know that the Robot Apocalypse has exactly one and only one horseman: computer programs that can write computer programs.

Artificially intelligent machines can’t ascend to godhood via the long-prophesied runaway spiral of continuous self-improvement until we invent a machine learning model that can code a better version of itself. We’re not there yet, and it’s not clear how far away such a development is, but as of the mid-2021 release of OpenAI’s Codex model, we’re a lot closer than we were just a few years ago.

Given that self-improving computer programs would likely be the most important human invention since writing, there is no other part of the AI content generation revolution that’s worthy of more study and careful scrutiny than generative models that output code.

And of all the new ML-powered programming offerings in this growing ecosystem, Replit has the tools I’m watching most closely. No other programming platform is in a position to train models on a dataset that includes the following from legions of programmers and millions of projects:

- Real-time keystroke and clickstream data

- Detailed execution and performance data

- Character-level file changes

If you were going to design a platform for the express purpose of teaching machines to code, it would probably be a cloud-hosted IDE plus execution environment that looks a lot like Replit. So while most of what you’ll read in this article and followups is applicable to all AI code generation tools more generally, I’ll be focusing on Replit’s toolset because right now it’s the richest and most advanced, and has the most potential for advancing the state-of-the-art.

In this article series, I’ll walk you through the following topics:

- What ML code generation can do right now.

- Types of programming work this tech might be used for in the near-to-medium term.

- The possible (non-singularity) economic, technical, and cultural implications of the widespread adoption of ML in software development.

Who these articles are for, in order of focus:

- New programmers who are just getting started and don’t have a grasp on the history of the field and how it has evolved to the present point.

- Non-programmers who are curious about what this tech can and can’t do.

- Experienced programmers who haven’t yet tried any of the new ML-powered coding tools and want to understand what they offer both now and in the future.

The five eras of programming

We all know that programming started back in the olden days with punch cards and people flipping levers and whatever other kind of stuff you can go watch a Ken Burns documentary about. While I give honor to all those who labored in sterile labs and offices at the dawn of the computing era and were more fabulously dressed than the Cheeto-fingered nerds who eventually followed them, I’d like to start my own discussion of the history of computing with the era we’re just now emerging out of, which is #3 on the list below:

Programming eras:

- Academics and engineers with mainframes and minicomputers

- Cowboy coders with personal computers

- Social coding + cloud + specialization

- ML-powered pair programming

- 🤯🚀🤖

I came up as a programmer in the PC-powered golden age of the cowboy coder — the hero hacker who authored the first version of some piece of software that changed the world. I eventually made the transition to the second era, which featured the rise of GitHub, the adoption of agile programming practices, and all the stuff that made programming more amenable to “day job” treatment.

It was during this time that a kind of Weberian routinization of charisma took place but in the realm of coding. Success in software projects steadily shifted from being about the unique genius of cowboy coders to being about communication and collaboration among a group of competent professionals of varied backgrounds and skill levels. This shift had three key enabling components:

- Social coding meant that your code needed to be readable, testable, and documented. You’re not just coding for some specialized system, but you’re also coding for other humans who may come to a project after you, or who you may be sharing solutions in venues like StackOverflow.

- Cloud meant that a lot of development work was about interacting with APIs. A modern web app became a kind of meeting place where multiple APIs for different SaaS products could be mixed and matched underneath layers of business logic and front-end code.

- Specialization meant the rise of back-end engineers vs. front-end engineers or people who were really good at particular kinds of problems (scaling, dealing with storage, front-end optimization, etc.)

I lay out these three elements of the third era of programming, which I’d date from maybe the 2008 launch of GitHub to the 2020 release of OpenAI’s Codex model in private beta because the fourth age of programming will see each of these areas revolutionized.

Machine learning models have much to offer each of the three parts of the third age, as we’ll see in the following sections.

Creating a modern web application

On a practical level, creating a modern web application involves a whole lot of the following kinds of work:

- Looking up how to talk to an API, either via a language-specific library or a REST API, and then writing code that makes the correct calls in the correct order.

- Generating boilerplate and scaffolding to initialize a new app, configure a new library in an existing app, or expand an existing app.

- Understanding code that was written by someone else, either some example code on StackOverflow or earlier code from the codebase you’re currently working in.

The first item on the list can take up quite a bit of the time of a junior or mid-level programmer because you have to know where to look for and how to read the relevant docs. This search and rapid comprehension work is the kind of thing you can get a lot faster at as you do more of it. At some point, you end up having done so many repetitions of this read-comprehend-retype loop that your instincts will tell you what the correct code should look like in most situations – the lookup activity is still necessary, but it’s mostly about confirming what your instincts already told you and about naming things properly.

Programmers are also constantly looking up and retyping the correct command-line incantations to get the particular permutation of boilerplate or scaffolding required for your app or feature. As with APIs and libraries, you can expect significant speedups with practice.

Finally, reading and understanding someone else’s code is also a matter of gaining fluency with a specific skill that gets better with practice. You’ll do a lot of this when you work on an existing application, but you’ll also do it constantly when writing new code because you’ll need to learn from reading code samples and poking around in test suites for popular libraries and APIs.

None of these kinds of labor require enormous mental horsepower. Smarter people will improve at these practiceable skills more rapidly than the less smart, but everyone is going to end up at more-or-less the same place, in the end.

We can reframe the three types of work mentioned above in terms of types of mental activity, in order to make it easier to map onto machine learning’s capabilities:

- Reading and rereading code, docs, forums, and StackOverflow, so as to mentally buffer enough of the latest version of all of it to do steps 2 and 3 below.

- Pattern-matching new programming problems with previously read problem/solution pairs.

- Retyping, in slightly tweaked form, some (pattern-matched) parts of what you’ve read to fit your current programming problem.

Ultimately, there are many of us — I’ve very much been there as a contract programmer and a startup CTO — for whom much of the work of software development is dominated by those three activities. It’s fortunate, then, that there’s a natural fit in the above activities for generative machine learning models, where the models are trained on large volumes of existing text, and can then do pattern-matching (aka “inference”) on novel inputs in order to do guided generation of some transformed, context-appropriate version of the training data.

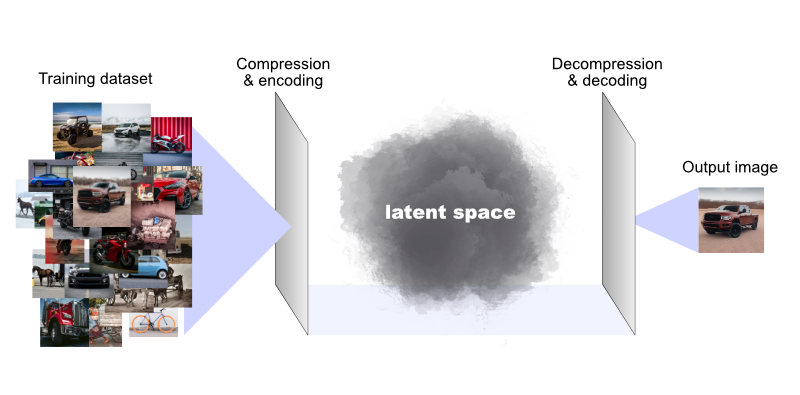

To revisit some concepts from my intro to generative AI, we can now make models where the latent space maps to possible computer programs (instead of it mapping to possible images, strings of natural-language text, sounds, etc.). So by searching latent space via a prompt or some other input, we can uncover interesting and useful blocks of code that make computers do things we want them to do.

For another way into this concept, take a statement that was popular in the early days of open-source software, and is currently making a comeback in web3: “code is speech.” To the extent that code is speech, then any model that outputs useful, meaningful, structured chunks of language that humans can interpret can also be made to output useful, meaningful, structured chunks of language that machines can interpret as commands.

This sounds like fantasy, but it’s actually being done right now. The results are real, and they’re spectacular.

Nice read on reverse engineering of GitHub Copilot 🪄. Copilot has dramatically accelerated my coding, it's hard to imagine going back to "manual coding". Still learning to use it but it already writes ~80% of my code, ~80% accuracy. I don't even really code, I prompt. & edit. https://t.co/kvQTOex9Qj

— Andrej Karpathy (@karpathy) December 30, 2022

Coding with Replit and the current state-of-the-art

The cloud-hosted programming platform Replit has an excellent, advanced set of ML-powered tools that can substantially reduce the time programmers spend reading, pattern-matching, and re-typing.

There are four main tools that are publicly available right now as part of Replit’s Ghostwriter suite of ML-powered programming tools: generate, explain, transform, and autocomplete code.

If you've used the popular Stable Diffusion AI image generator or have read my in-depth introduction to it, each of Replit's ML-assisted programming tools has a direct analog to what you can do with that image generator:

- Generate is the code analog of the standard

text2imageoperation we're all familiar with, where a text prompt gives you a file from a location in latent space. - Explain works a little bit like Stable Diffusion's image-to-text capability, where you can feed it a generated image and a seed and get back the corresponding text prompt. This feature isn't widely known since it's not supported in any of the GUI tools, but the model can do it. More generally, you can use many text-to-image models in reverse to generate a textual description of the contents of the image.

- Transform is the code equivalent of Stable Diffusion's

img2imgfeature, where you're transforming one input image into another with guidance from a text prompt. - Autocomplete is also like

img2imgbut without the explict prompt guidance.

Let’s look at each of these in more detail.

Generate code

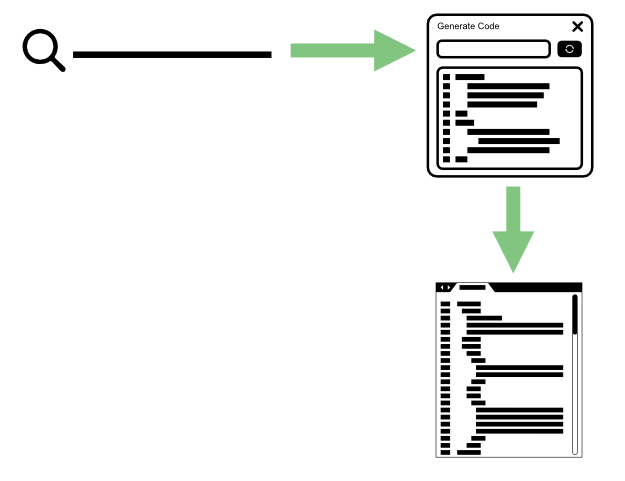

As I said above, Replit's “generate code” tool is very much like what I described in this intro to Stable Diffusion, but instead of turning a text prompt into an image, it turns a text prompt into a program in whatever language you’re using in the file you’re editing.

Generate Python

The main thing this feature does for coders is it lets them tap into the model’s memory (latent space) for code boilerplate and scaffolding, instead of tapping into their own memory.

Instead of going out and reading all the docs for, say, writing a Discord bot in JavaScript, and then buffering that information in my own brain (or on my computer’s clipboard) so that I can tweak it to fit my needs, I just pull the starter code from the model’s memory. Once I get the code into my editor, I can do the last bits of tweaking and transforming it, myself.

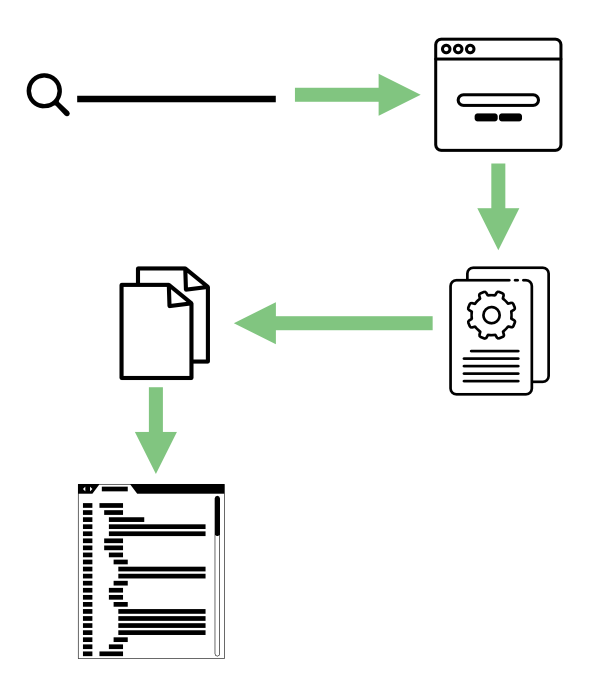

What “Generate Code” does, then, is to turn this:

Into this:

As I described in my intro to AI content generation, an input prompt for an ML model is essentially a search query, so I’m still turning queries into code just like my non-AI-assisted programming peers — I’m just doing it faster and more directly from right within the editor.

Explain code

Replit’s code explanation feature gives you a short text description of what a highlighted block of code does.

Explain code

In its present state, this tool strikes me as most useful for programmers who are new to a language and trying to grasp the basic mechanics of what an undocumented function is doing.

However, what I usually want to know when looking at a piece of code is not “what’s happening?” but “why is this happening?” And the answer to that “why” question always involves some critical context that’s present in some other file of the application.

In other words, instead of an English-language walkthrough of what a block of code does when it executes, I typically want an explanation that sounds more like, “This is an event that’s loaded on the page is loaded and fires when the window scrolls down past the target div, so that the next page of items can be retrieved from the database and inserted into the page. The function retrieves the current page from the DOM, sends a query to the server using the current page and current query string, and then calls a function to render the new items with the results from the query.”

This kind of higher-level description, where it’s explaining both the “what” and the “why” of a function within the specific context of the application, seems very likely to be within the reach of a tool like this, but it’s going to take some doing. Right now, there’s just no way to get the amount of context necessary for such an explanation into a pre-trained model — input token windows on current models aren’t nearly large enough to fit a meaningful portion of a real application’s code base.

To make the code explanations truly a substitute for pairing with a human programmer who deeply understands the code you’re looking at, my guess is we’ll need models with token windows that are at least in the hundreds of thousands, if not the millions.

Transform code

This tool allows you to tweak existing blocks of code by renaming variables, wrapping HTML in tags, wrapping JavaScript functions in a promise, converting older JavaScript dialects to something more modern, or other types of tweaking and cleanup.

Convert to modern JS

You can even use this tool to translate code from one language to another, which for some of us is even more useful than having it explained in English. For instance, I’m an advanced rubyist but a python newb, so this language translation ability is helpful for me when I’m messing with ML-related Jupyter notebooks on Google Colab.

Autocomplete

Replit’s autocomplete tool uses the code and comments you’ve already written to infer what code should go next, and then suggests that code for you.

Ghostwriter

The relevant Stable Diffusion analogy here is image2image, where the model is taking the text that’s already in a file, and as you type it’s doing a live search of latent space for code that’s adjacent to what you’ve typed and what you’re typing.

Right now, there are a few limitations to this tool that are related to the fact that its suggestions consist of the output of a search of latent space done via a limited input token window:

- The tool doesn’t automatically infer the correct variable names, so when you accept the autocompletion you’ll have to change those, yourself.

- Current code suggestion tools, which are based on documentation, are already pretty good, so the performance delta between those and ML-powered autocomplete isn’t always as noticeable right now as it will be in the future.

Again, a much wider input token window will help with both of the above,

Conclusions

The current generation of generative coding models is searching latent space for the programming equivalent of paragraphs of text or pictures — there’s a kind of boundedness here, where the models discover discrete code objects that fits specific contexts.

Contrast this to what we eventually want them to do, which is to reason their way from a problem to a solution by conceiving of and then implementing in code a sequence of steps that follow one from the other.

In other words, currently, it’s up to you as a developer to game out the steps involved in solving a problem — when it comes to implementing each step, you can search latent space (instead of searching Google) to find the right block of code. But latent space isn’t (yet) going to give you the steps, themselves. That’s because causality is still a hard problem in ML and it’s still difficult to get models that can reason capably about cause/effect relationships in order to solve completely novel problems.

That said, there have been some successful attempts to get LLMs to generate sequences of steps or ideas based on past training inputs, so there’s still plenty of coding magic to be uncovered within the existing LLM paradigm that powers the current generation of tools.

In the next article, we’ll take a look at the lifecycle of an application with a view to imagining the kinds of things ML can do for programmers in the near- to medium-term.